Dealing with “The Dark Side” of Human Behaviour

I come across many articles providing so-called tips on how to handle “toxic” or “difficult” people, or glorifying the “positive side” individuals displaying harmful or psychopathic behaviour traits can bring to their environments, especially in business. I do not hold such views and believe them to be irresponsible and damaging. It is also very rare for these “tips” in popular psychology articles to actually really help those at the other end of such behaviours. When one person displays very harmful behaviour, mistreats others, is controlling, and has been permitted to do so systematically and over time, it is not a relationship system one can easily “get out of” in any environment, let alone “unscathed”. A different approach is needed to address these challenges and the effects on those impacted.

The aim of this series of articles is to raise awareness of “The Darker Side” of human behaviour in various environments, starting with “The Dark Triad” of personality traits. We’ll shed light into various forms of psychologically abusive behaviours, which might go undetected in certain environments in an article we co-authored with an expert in this field, offer possible approaches to addressing the challenges individuals with those harmful traits pose as well as suggest a path of change to those impacted by the behaviours. As a former HR practitioner, I do appreciate the complexities involved. This is a topic I currently research globally.

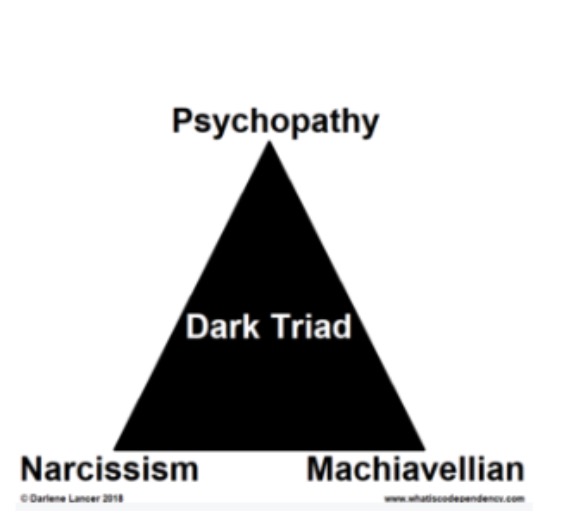

What is the Dark Triad and what are the traits?

As far as I know, the term “toxic” is not a psychological construct that we psychologists can measure and neither is the term “difficult” (let me know if upon reading this you do know of research). Articles exist by Pelletier (2010) and Singh et al. (2017) but evidence is scant.

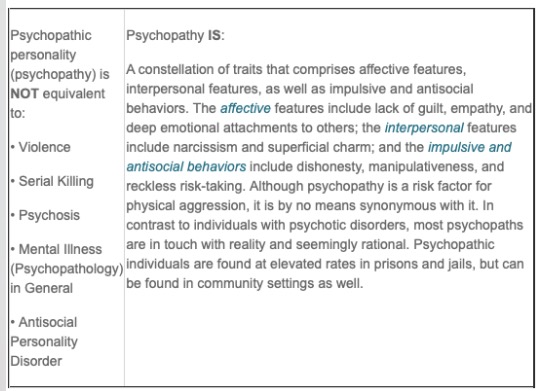

We do, however, refer to “The dark triad” of personality traits of “Narcissism, Machiavellianism and Psychopathy”,which we can measure. Being at the other end of, or involved in, any relationship system (professional or personal) with individuals scoring high on these three traits is not only a “win-lose” situation but creates immense long-lasting distress and suffering, psychological, physical and financial, long after the sufferer has exited the relationship and/or environment. Permitting these individuals to continue adopting these behavioural traits poses a real threat to any environment they operate in, especially if they are in leadership or hierarchical positions of power where there is a structural imbalance of power between the person deemed ‘follower’ and their ‘leader’.

“Not all psychopaths are in prison – some are in the board room“

By Robert D. Hare, 2002

Photo credit: “Christian Bale in ‘American Psycho’, courtesy LionsGate”

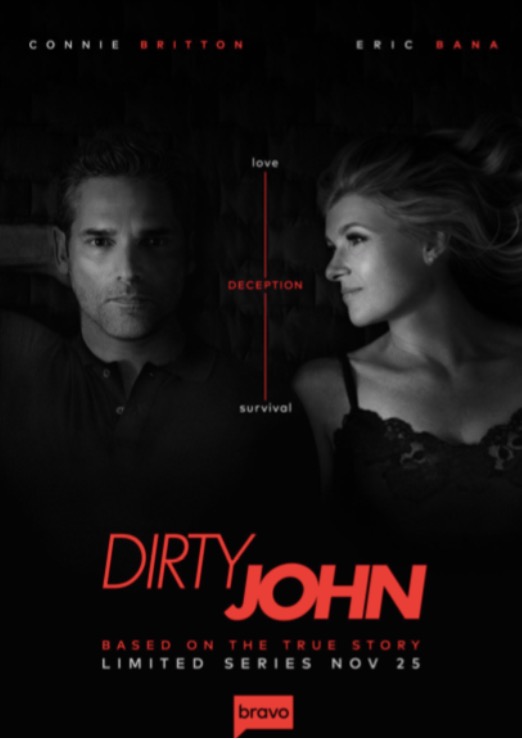

The Dark Triad of personality traits might have now truly entered the world’s popular cultural lexicon, thanks, in part, to Anthony Hopkins’ brilliant and chilling portrait of Psychopath Hannibal Lecter in “Silence of the Lambs”, Christian Bale in “American Psycho” (photo above), the hugely popular Netflix TV series “Dirty John” or the darker “Killing Eve” as well as the sadly very real case of President Trump. In their book “The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President” mental health experts urge President Trump to be assessed mentally and neurologically following very concerning behaviours on the continuum of the triad, and what they observe to be “dark” psychological processes at work. There are criticisms of the dark triad theory, namely that the tests do not use enough criteria for assessment, that the dark triad has been carried out on narrow groups leading to a lack of generalisation. However, it is my view that the concept and theory can be applied accurately.

What if you cross path with psychopaths on your way to making a cup of tea at work?

Research shows that all of us in the general population will be somewhere on the continuum in the three traits and this does not mean we meet the clinical diagnosis of psychopathic, narcissistic or machiavellic disorders.

Machiavellianism can be termed as “the manipulative personality” (Christie & Geis, 1970), Narcissism includes grandiosity, entitlement, dominance, and superiority and Psychopathy has been defined as demonstrating high impulsivity and thrill-seeking along with low empathy and anxiety. These traits have also been shown to share “a socially malevolent character with behaviour tendencies toward self-promotion, emotional coldness, duplicity, and aggressiveness” (Paulhus, 2002). These traits often also overlap and share a common core of “disagreeableness”. “The Dark Triad” is contrasted with what has become to be known as “The Light Triad” of behavioural traits (Kaufman et al. (2019) which can also be measured by a 12-item Light Triad Scale (LTS) assessing loving and beneficent orientation toward others consisting of three facets: Kantianism (treating people as ends unto themselves), Humanism (valuing the dignity and worth of each individual), and Faith in Humanity (believing in the fundamental goodness of humans).

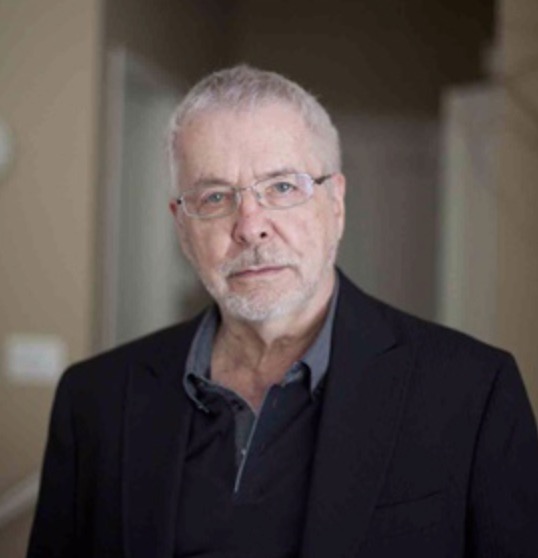

“People tend to think of Psychopaths as criminals. The majority of Psychopaths are not criminals”

Robert D. Hare

Robert Hare is the expert in this field, former University of Columbia researcher, and the creator of the gold standard psychopathy checklist “The Hare Psychopathy Check List-Revised”* (PCL-R, if you are interested in reading the traits, check under references at the end of this article) used by researchers, forensic clinicians and the justice system to identify the traits and behaviours displayed by psychopaths.

Hare’s “Not all psychopaths are in prison – some are in the board room” now rather “famous” quote created a sensation at the time in 2002 when he casually uttered it in response to a question by journalists at a Canadian Police Association meeting in St. John’s, Newfoundland where he was speaking.

Hare has long maintained that media headlines, popular TV and film crime shows, as well as the public’s fascination with the psychopathic criminal result in he public only receiving exposure to “psychopathy” from these media and being considerably misinformed. This is also the case with business professionals “because of the difficulty for researchers to obtain active cooperation from corporations and organisations” says Hare. However, as in this 2010 study, there are exceptions, especially with forward thinking organisations focused on corporate responsibility and wellbeing.

According to his research, 1 in 100 people are psychopaths and they tend to blend in, and up to 4 percent of corporate workers are psychopaths. I am advised that he is in the process of validating a research tool that HR and corporate colleagues could use to screen for psychopathic traits. I have not been able to obtain further information at this stage and look into the legal ramifications.

What does this look like in real life? A psychopathic abusive worker will tend to be in a position of relative power or work at being in one. A manager perhaps, for example, will include you in events some of the time, but not other times (when these might be beneficial to you) demonstrate apparent caring some of the time but lash out at you other times, wait until you go on extended leave to network on your behalf or maybe take the credit for your work at events, plant rumours and gossip, turn people against each other, belittle you, isolate you, and shift their persona like a chameleon to isolate or remove you. They might display other of the triad traits and use a variety of other behaviours and techniques, I will be sharing in other articles I am co-authoring with a colleague. They will do this slowly over a period of time without you or their own management ever knowing. If they were compared to a disease they would be a difficult strain of a virus or flu starting with very mild symptoms but reaching unexpected highs some of the time, and not others.

The psychopath’s, narcissist’s and machiavellian’s chief skill is at manipulating perceptions: what might look like good influence and persuasion skills, will appear like the mark of an effective leader, charm and grandiosity will be seen as self-confidence or charismatic leadership style, good presentation, communications, and impression management skills also continue to reinforce this image of the “true leader”.

“We need research in the prevalence, strategies, and consequences of psychopathy in the corporate world. We need an empirical base for conducting and evaluating research on the more high-profile miscreants who have wreaked financial and emotional havoc in the lives of so many people. ”

David R Hare, 2010

In one 2010 study, Hare and colleagues had the opportunity to investigate psychopathy and its correlates (lifestyle, antisocial, affective elements) in a sample of 203 corporate workers selected by their company to undergo a management programme and had to be evaluated. They found that “psychopathy was positively associated with in-house ratings of charisma/presentation style (creativity, good strategic thinking and communication skills) but negatively associated with ratings of responsibility/performance (being a team player, management skills, and overall accomplishments).” Moreover they found that “some with very high psychopathy scores were high potential candidates and held senior management positions: vice- presidents, supervisors, directors”. However, the most disturbing finding in Hare et al. (2010) perhaps was that the antisocial element they observed in those executives scoring high on psychopathy moderately predicted increased ratings on the charisma/presentation traits of those executives. These are considered valuable assets in high-level executives. This might highlight that when an executive displays charm and charisma a failure to follow the rules can impress others. This adds evidence to the body of research, to reports in the media and other business reviews, which have indicated that some psychopathic individuals manage to achieve high corporate status (Babiak & Hare, 2006) and they are often admired.

What we know from the research available is that they tend to have a certain mind-set, are in positions of relative power, which has given them certain advantages they won’t let go of easily, will exert control over usually someone they consider ‘inferior’. They might suffer mental health issues but often their abuse is not correlated with their mental illness. Evidence shows that “abusive” people know who they can abuse, when to stop their abuse in certain contexts depending on who they decide is ‘inferior’.

“Although psychopathy, broadly speaking, reflects a fundamental antisociality (Hare & Neumann, 2008), some psychopathic features (e.g., callousness, grandiosity, manipulativeness) may relate to the ability to make persuasive arguments and ruthless decisions, while others (e.g., impulsivity, irresponsibility, poor behavioral controls) relate to poor decision-making and performance.”

Robert D. Hare, 2010

The persons at the other end of this extremely damaging abusive behaviour might be “baffled” and take the abuse personally thinking “it is ‘their fault and that they must have done something wrong’, might be ‘vulnerable’ (emotionally, physically, mentally, financially) at a particular stage in their life for whatever reasons meaning they might tolerate some of the unacceptable behaviour, are afraid or unable ‘to confront’ and ‘speak up’ even in the presence of ‘policies’. They will need support and validation in doing so. It is not their job to speak to the abuser.

Whilst the above might paint a gloomy picture, there is a cultural shift in not glorifying the psychopathic and abusive traits in business. What research (including my own and that of colleagues) shows, is that by highlighting the devastating effects on individuals and organisations impacted (adverse effect on job performance, productivity and psychological wellbeing), we can end the myth that “a bit of psychopathy is good for business”. We can collectively start shifting the culture ensuring that everyone’s rights, for dignity and wellbeing, are upheld. Researcher O’Boyle has studied the effect of the dark triad on job performance. He maintains “It’s potentially damaging when we start to glorify what are socially adverse behaviours and attitudes. People who show psychopathic behaviours are not people you want to helm a company.”

In the next series, we’ll delve deeper into some of the behaviours and strategies displayed by those who are generally known as “abusive” to coercively control others in various environments. As Herman pointed out “We forget that “although it is often dominant individuals who influence the making of societal rules, it is also often dominant individuals who break them”.

References

Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. New York: HarperCollins.

Babiak, P, Craig. S., Neumann, C.S., & Hare, R.D (2010) Corporate Psychopathy: Talking the Walk. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 28: 174–193 (2010). DOI: 10.1002/bsl.925

Hare, R. D. (1985). Comparison of procedures for the assessment of psychopathy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 7–16.

Hare, R. D. (1991). The Hare psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R). Toronto, Ontario: Multi- Health Systems.

The checklist’s 20 items include glibness/superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, need for stimulation/proneness to boredom, pathological lying, conning/manipulation, lack of remorse/guilt, shallow affect, callousness/lack of empathy, parasitic lifestyle, promiscuous sexual behavior, early behavior problems, lack of realistic, long-term goals, impulsivity, failure to accept responsibility, many short-term marital relationships, juvenile delinquency and criminal versatility.

Herman, H. (2017). The Game of Life, chap 9 Alternate Human Behaviour, p139-p157. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805372-0.00009-2

Hogan, R. T. (2007). Personality and the fate of organizations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kaufman, S.B., Yaden, D.B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayama, E. (2019). The Light vs. Dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology.10, 467.

Lee, B. X., et al. (2017) “The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President”. Thomas Dune Books. New York. NY.

Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2008). Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 893–899.

O’Boyle et al. (2011) A Meta-Analysis of the Dark Triad and Work Behavior: A Social Exchange Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 97(3):557-79.

Paulhus, L. & Williams, K.M. (2002) The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality. 36, 556–563.

Pelletier, K. (2010) Leader toxicity: an empirical investigation of toxic behaviour and rhetoric. Leadership. DOI: 10.1177/1742715010379308

Singh, N. et al. (2017). Perceived toxicity in leaders: Through the demographic lens of subordinates. Procedia Computer Science 01022(2(021071)7)00101–40–01021

www.psychopathysociety.org/en